Selected broadcast reports from Germany, Austria, and Switzerland

Radio is quite a phenomenon. Invented over 100 years ago, it continues to be an important mass medium (even though TV and the internet have certainly come to dominate). In Germany, some 35 million people – or 30% of the population – listen to radio programs every single day. Stories revolving around the airwaves themselves are frequently published by other media. A quick dive into the vaults of EUscreen uncovers an astonishing number of 'radio stories' on European TV channels. Here's a selection of favourites from the German-speaking world.

Duel on the Pizzo Groppera

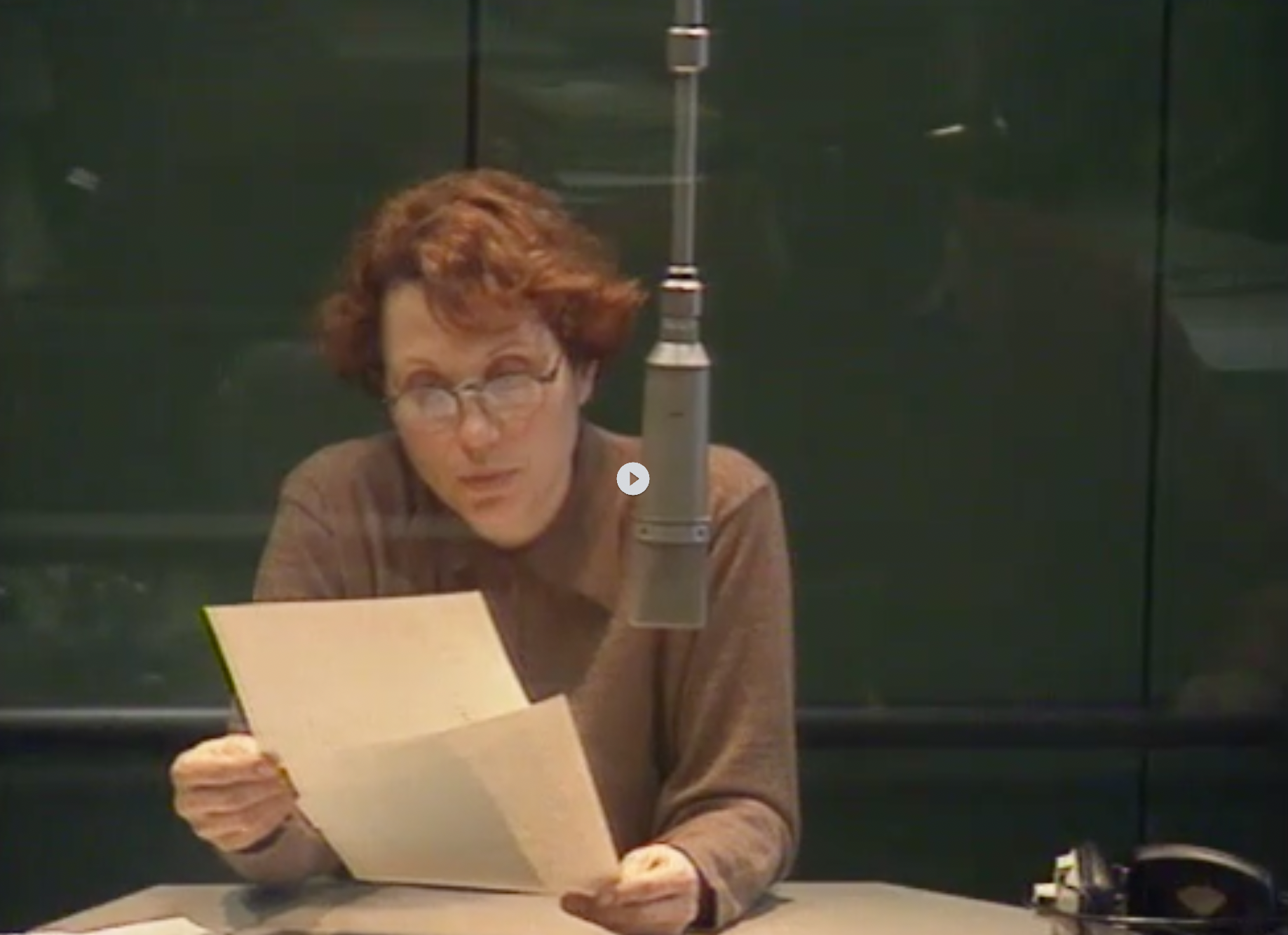

Titled like a Spaghetti Western, this full-length SRF documentary tells (the first part of) the story of Radio 24, Switzerland's private broadcasting pioneers. Pizzo Groppera is the name of an Italian Mountain in Lombardy. It is almost 3000m high, located close to the Swiss border and the Zurich metropolitan area, and was therefore considered a perfect location when Roger Schawinski and his crew decided to set up their own FM station in 1979 (with a studio in Cernobbio/Como).

Back then, Swiss law did not allow private broadcasting – so the government in Bern immediately labelled Radio 24 a pirate operation and tried its hardest to shut it down. Produced in 1980, Duel only depicts some of the events surrounding Radio 24, which can be summarised like this: lots of debates on both sides of the border, legal sabotage by the Swiss government (no weather and road reports for you!), a "free radio" movement, mass demonstrations in Zurich, widely supported Radio 24 petitions, a number of raids by the Italian (!) police, and – finally – the legalization of Radio 24 (and all private broadcasting in Switzerland), as well as the move of the station and the studio to Zurich. In the age of YouTube channels and Spotify podcasts it's hard to imagine that the launch of a private radio station could create such turmoil, but in the late 70s and early 80s the Radio 24 venture was a pretty big deal.

IFA and the future of radio (in 1989)

IFA (= International radio exhibition Berlin) is one of Europe's leading tech shows and usually a good place to learn about current trends in broadcasting and digital media. In the short report featured above, RIAS (closed in late 1993 and subsequently made a part of DW and Deutschlandradio) covers the official 1989 DSR kick-off by Christian Schwarz Schilling (then Germany's minister responsible for telecommunications). It is no surprise if the term DSR does not ring a bell.

First prototyped in 1982, officially adopted in 1984 and launched with pomp and circumstance five years later, DSR was supposed to drastically improve broadcasting quality and usher in the era of digital radio in Germany. In retrospect, the project was a big failure, though. Receivers were expensive, few stations supported the new standard (DSR started out with a bundle of only 16 radio programs), alternative technologies prevailed, and DSR was officially shut down in January 1999. DAB/DAB+ later on became the first successful and sustainable digital radio standard in Germany. However, even in 2022, classic FM stations are still around.

Sines Relay Station

Back in the heyday of shortwave radio, international broadcasters depended on so-called relay stations, i.e.: installments in remote places that would receive broadcasts from the organization's headquarters and then pass them on – relay them – to target areas that could otherwise not be reached.

In a fascinating, very technical 1993 report, a DW journalist pays a visit to his broadcaster's relay station in Sines, Portugal. Opened in 1970, the site had recently been upgraded with two modern antennas. Among other interesting radio facts, the report explains why a place like Sines was picked to reach audiences in Eastern Europe and Russia: Because of the particularities of short wave radio and so-called 'dead zones', you actually needed to go west in order to broadcast east.

The report also features incredibly geeky terms like 'vertically polarized logarithmic-periodic antenna' – which will not be discussed in detail here. The relay station in Portugal was closed in late 2011, but it is fondly remembered by older engineers, and it lives on the collective DW memory: One of the conference rooms in the broadcaster's Bonn headquarters is called 'Sines'.

Belgrade via Cologne

The B92 story is another 'radio on tv' report by and about DW. But first and foremost, it's a story about freedom of expression and solidarity among journalists and media managers: In December 1996, Serbian radio broadcaster B92 was banned from the airwaves by the Milošević government, which had been extremely unhappy with the fact that the station had continuously covered swelling student protests against nationalist propaganda or election fraud. What followed after the shutdown was international outrage and a wave of solidarity.

Several radio stations – among them DW, then based in Cologne – decided to take B92's programs and broadcast them via their own network. Needless to say, they could not tap into terrestrial frequencies in Belgrade, but the combination of short wave and satellite radio (and early internet broadcasting ) literally sent a strong signal. It only took a couple of days until B92 was officially back. At least one crisis in the Balkans had been averted.

Ö1 Anniversary

In case you are struggling with the umlaut: It is a close-mid front rounded vowel. In this context, it stands for Österreich (= Austria), and Ö1 is simply one of the Alp Republic's national radio stations, operated by public broadcaster ORF. The above featured report on Ö1's 40th anniversary (which took place in 2007) is rather unspectacular. However, it features one great quote by the ORF's former Director General, Gerhard Bacher: 'I'll never forget when I first came to this building, in 1967, when everybody was like: "You know, TV is gonna kill radio broadcasting any day now." And I said: You're totally crazy. We'll actually have a great radio renaissance!'

Of course, Bacher was completely right. Even though TV became very successful in the 1960s/70s and the ORF also took to the internet a couple of decades later, its radio stations are still around and an integral part of the brand. In 2022, Ö1 celebrates its 55th anniversary.

To be continued!

Will there be more radio stories on TV (and in other media) in the future? That is very likely. Not just because old school radio is still a thing, but also because audio broadcasting constantly evolves and inspires web formats. Some argue, for example, that Clubhouse or Twitter Spaces is basically special interest talk show radio rebooted on social media. Last, but not least, radio is the basis for a number of groundbreaking technologies – like WiFi, 5G/6G, or space photography. There are lots of reasons why people will want to talk on and about the airwaves for years to come.

This blog is part of the editorials of Europeana Subtitled, a project which enabled audiovisual media heritage to be enjoyed and increased its use through closed captioning and subtitling.