The 18th century play La Dalmatina by Carlo Goldoni - sometimes referred to as 'the Italian Molière' - is a striking illustration of the relationship between Venice, Istria and Dalmatia.

Since the late middle ages, the relationship between Venice, Istria and Dalmatia has been complex.

In addition to quarreling for political, economic and religious reasons, and despite the dominant hierarchical position of Venice, there was also a mutual dependency: alliances with Venice offered eastern Adriatic cities trade opportunities and protection, while on the other hand the coastal region was indispensable for the Venetians to maintain their trade monopoly.

This spectrum often created internal tensions: in some cities, for instance, discord arose within the population that partly sympathized with the Venetians, partly with the Croats of the hinterland.

The tragicomic play conquered the Venetian stage in 1758, leaving the audience so pleased with Goldoni that he notes in his memoirs 'they showered me with praise and gifts'.

The play would become one of the best known of Goldoni’s texts, and was particularly successful because of the sentiments of patriotism expressed in it.

In La Dalmatina, Dalmatia and Slavic characters were seen as semi-oriental elements which, combined with the Moroccan setting, placed the play in the vein of the exoticism that was fashionable at the time.

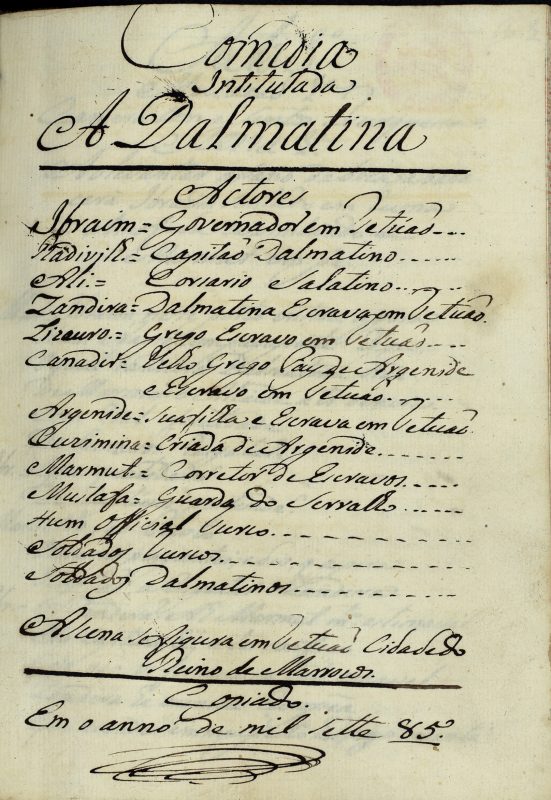

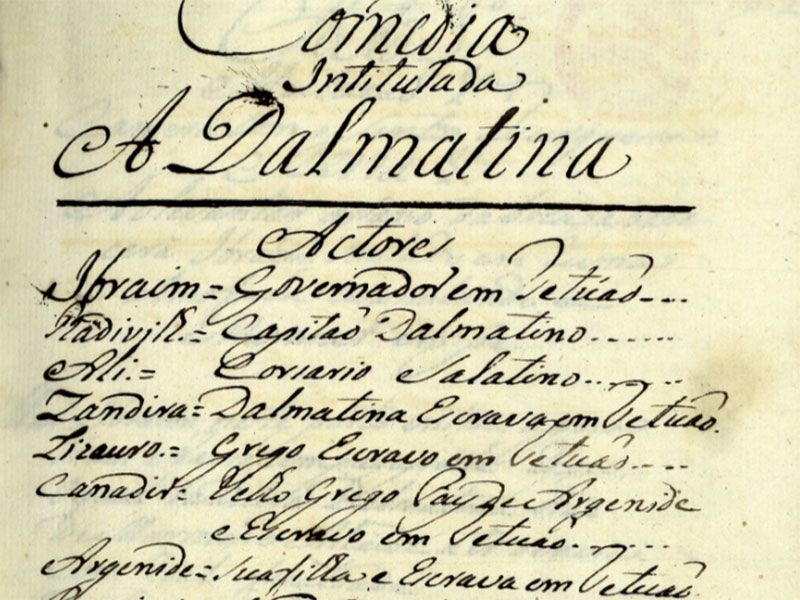

Comedia intitulada A dalmatina, Carlo Goldoni, Public Domain, Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal

In his memoirs, Goldoni confirms the Venetians' particular attitude toward the Dalmatians by stating that they in fact felt great appreciation for their 'counterparts': they acted as 'antemural Christianitatis', helped to protect the Italian properties and secure their princes.

In the foreword to an edition of La Dalmatina, Goldoni stated: 'The [piece] is about a loyal nation worthy of La Serenissima.'

Although some nuance is necessary, the influence of this political-economic situation on the cultural history of both Italy and Croatia can’t be overstated: Istria and Dalmatia have - perhaps more than any other regions - absorbed the influences of Renaissance and humanistic Italy.

Many artists from the Adriatic East Coast enjoyed their training in Venice, or were active there for at least part of their career. In turn, they have considerably enriched the artistic landscape of Venice.

Goldoni himself would not remain in Venice all of his life.

He migrated to France, directing the Comédie-Italienne in Paris for several years. From 1764 onward, this great innovator of commedia dell’arte and opera buffa retired to become a teacher to the princesses of Versailles. Yet he died in poverty after having been deprived of his royal pension, just one day before a restitution would be granted.

Goldoni left behind a noteworthy and much-cited autobiography, titled Mémoires. Today he is remembered not only through his creations, but also with several landmarks in his native city: a statue sculpted by Antonio Dal Zotto, the Ponte Goldoni bridge and the magnificent Teatro Goldoni - the oldest, still existing theatre in the city.

This blog post is a part of the Migration in the Arts and Sciences project, which explored how migration has shaped the arts, science and history of Europe.