How text has influenced how, what and why we read

The shape of the text has influenced how, what and why we read. This is the first blog of the Rise of Literacy project, where we take you from papyri to universities, exploring literacy in Europe thanks to the digital preservation of precious textual works from collections across Europe. 2000 years ago, texts were written on scrolls of papyrus. Only between the 2nd and 3rd centuries, the codex - the bound book as we know it - became common. In Ancient Greece and the early Roman Empire, reading meant holding such a volumen with both hands and unrolling it from right to left.

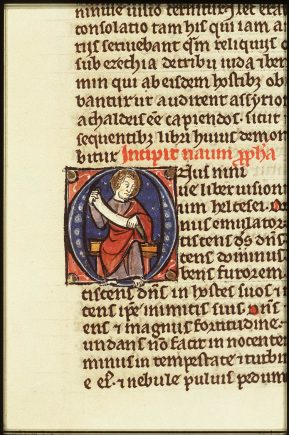

The prophet Nahum holding a scroll. Mathurin atelier, follower. National Library of Netherlands, public domain

The prophet Nahum holding a scroll. Mathurin atelier, follower. National Library of Netherlands, public domain

If you think that was hard, consider that punctuation - as we know it - didn’t exist! Words could be separated from one another with a full stop or even not separated at all (_scriptio continu_a). Nonetheless, reading was a popular practice, even amongst the less educated. It was common to read aloud in public: educated slaves, landlords or authors themselves would read aloud following rhetorical rules to give the right inflexion. The important art of oratory is described by authors like Quintilianus ( c. 35-96 AD).

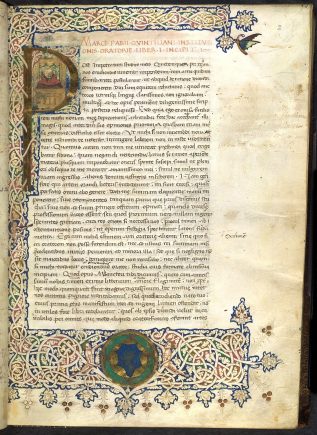

Quintilian from BL Burn 244, f. 2. Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (index Quintilian). British Library, public domain

Quintilian from BL Burn 244, f. 2. Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (index Quintilian). British Library, public domain

Quote from Quintilianus, Institutio Oratoria

“There is much that can only be taught in actual practice, as for instance when the boy should take breath, at what point he should introduce a pause into a line, where the sense ends or begins (...) and when he should speak with greater or less energy”

Contrasted with the overtly public practice of reading aloud, the early Medieval Christian way of reading (IV-XI cent.) was remarkably different. The book, now in the form of a codex (the book as we know it), was the shrine of the word of God. Reading became slower, more personal and silent. People used to read a small number of texts several times, possibly learning them by heart. This explains the prominence of the Book of Hours, small books containing Psalms, prayers and religious offices collected for individual worship (see our collection on Europeana). In this era of low literacy, official as well as religious texts were still written in Latin across almost all of Europe, but not everybody could understand Latin. Irish scribes in particular helped to further the reading and understanding of Latin texts by introducing new features, like the more obvious division of words and sentences via punctuation marks and the litterae notabiliores: from simple letters in a different color, to the large illuminated letters we commonly associate with illuminated manuscripts that highlight new chapters and paragraphs.

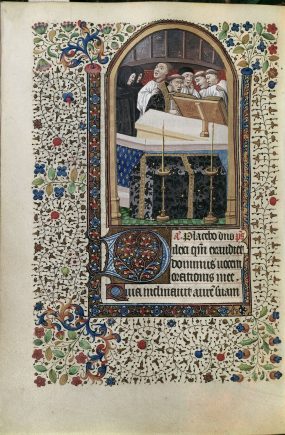

Church mass from BL Harley 2971, f. 109v. British Library, public domain

Church mass from BL Harley 2971, f. 109v. British Library, public domain

Quote from Hugh of Saint Victor, Didascalicon

“Therefore I beg you, reader, not to rejoice too greatly if you have read much, but if you have understood much. Nor that you have understood much, but that you have been able to retain it.”

The establishment of universities in the 12th century brought more remarkable changes. As now the book was read with an academic scope, the text was often displayed in two columns, allowing faster reading and leaving space for writing notes.

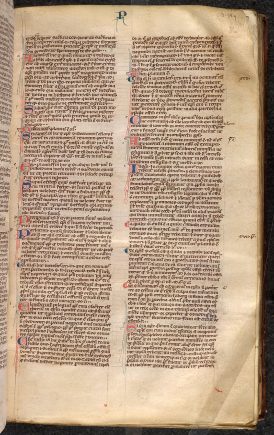

Pecia mark from BL Arundel 435, f. 36. Petrus de Salinis, Bartholomaeus Brixiensis, Guillelmus Duranti, and others. British Library, public domain

Pecia mark from BL Arundel 435, f. 36. Petrus de Salinis, Bartholomaeus Brixiensis, Guillelmus Duranti, and others. British Library, public domain

Written by Elisa Brunoni, Technologist, CNR-OVI, Italy.

References: Guglielmo Cavallo, Roger Chartier, Storia della lettura. Bari, Laterza 1995; Arsenio e Chiara Frugoni, Storia di un giorno in una città medievale, Bari, Laterza 1997